In my mind, Morris Lapidus always reigned supreme as the High Priest of South Florida Kitsch, in the most glorious sense. He was born in Odessa, then a part of Russia, in 1902. Lapidus came to New York as a small child, with his Jewish family, in order to escape the pogroms of the time. As a young man, he dabbled a bit in the theatre and ultimately graduated from Columbia in 1927. Let’s begin Architecture for the Soul- Morris Lapidus right here.

New York

Following his graduation from Columbia, Lapidus worked with Warren and Wetmore, a firm well known as Beaux-Arts architects. There, he did some work for the Vanderbilts before moving on to Ross-Frankel, retail architects. This is a critical point in understanding the extravagance that Morris Lapidus would later bring to his version of resort hotel architecture. In their obituary for Lapidus, The New York Times said this about his experience during this era:

During these years, working for several firms and later for himself, he supervised the construction of more than 500 stores, storefronts and showrooms for Lerner, Bond's, Howard Clothes and such shoe chains as Florsheim, Baker and A. S. Beck.

Did the drama and immediacy of retail store design serve as a launching pad for his “shock and awe” hospitality design style? I think the answer is easy.

The Fontainebleau Hotel, Miami Beach

In 1952, hotelier Ben Novack, who had purchased the old Firestone Estate on Miami Beach, commenced construction on the Fountainbleau Hotel. This property was destined to become one of the most famous hotels in the world, starring in more movies and TV shows than we can easily list. One of the many Fountainbleau back stories is the name itself. As legend has it, Novack and his wife Bernice settled on the property's name after an extended trip to France, including to the Palace of Versailles.

The selection of Lapidus as the architect is another cool story. According to the architect himself in the New York Times:

When Ben Novack announced that he was building the Fontainebleau, it appeared in the New York papers that I was to be the architect. But when I called him he said I wasn't chosen, that I never did a whole hotel and that he just needed a name at the time. It took me a year to convince him. I moved heaven and earth to get that job.

In hiring Lapidus, it was clear that Novack and his then partner Harry Mufson were hiring an architect to provide them with drama. In fact, according to Lapidus, while discussing a design plan and potential architectural style, Mufson said:

I don’t care if it’s Baroque or Brooklyn, just get me plenty of glamour and make sure it screams luxury!

This takes us to the notion of glamour in mid-century America. If the definition of glamour in 19th Century America arrived after a transatlantic journey from Europe, by the time Lapidus began designing the Fountainbleau, Hollywood served it up. Whether it was the over-the-top pre-war version or the more restrained post-war iteration, Americans craved a glam reality outside of their daily lives.

Morris Lapidus understood what his clients wanted for the Fountainbleau. He also knew what he had to do in transitioning from being a store designer in New York to being an architect on Miami Beach. He told us so below:

My whole success is I've always been designing for people, first because I wanted to sell them merchandise. Then when I got into hotels, I had to rethink, what am I selling now? You're selling a good time.

My first visit to the hotel was in 1981. In a sense, I was somewhat prepared. The concave shape of the structure, the very “Miami Beach in the 50’s” arrival area, the opulence of the lobby, were all anticipated….to a degree. Maybe I shouldn’t have known that essential scenes from the classic James Bond movie Goldfinger were filmed here. Then the Bond theme music might not have been stuck in my head. But I digress.

Years later, writer and critic Rhonda Lieberman described the hotel:

The place facilitates unspoken fantasies that you are Grace Kelly gliding through a tropical movie set, when in fact you may look more like Alice Kramden.

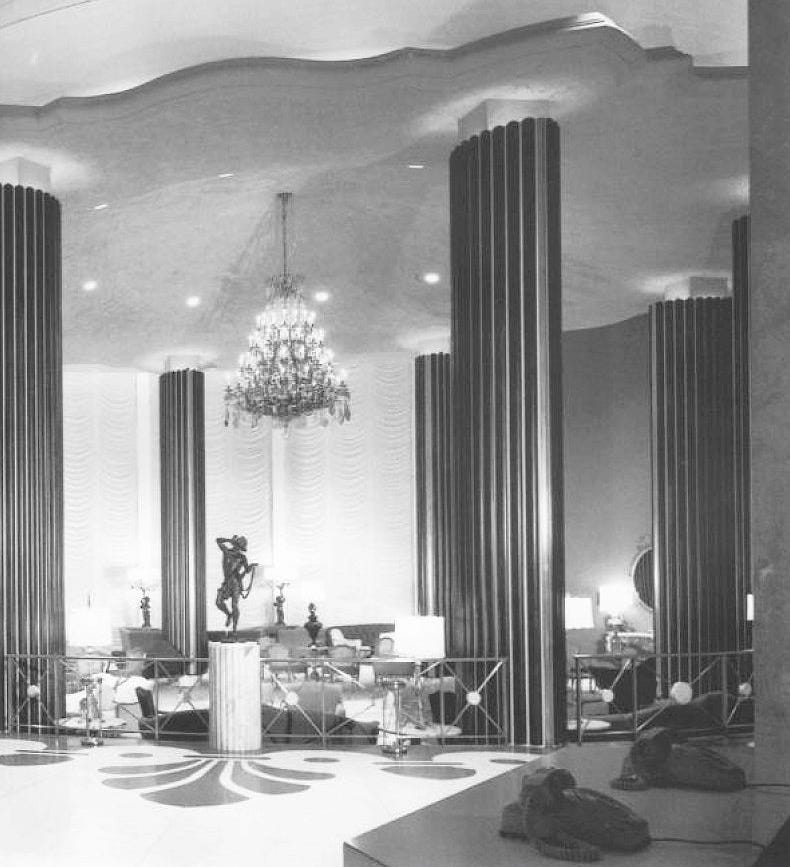

The idea that Lapidus intended to create a Hollywood movie set is reinforced when you take a look at the images above. There, you will see the famous “staircase to nowhere” where guests could take an elevator to the top of the staircase, then theatrically descend in a dream sequence to imagined “oohs and aahs” from admiring fans. Also in evidence are the bowtie patterns in the stone floor. As legend has it, they were signature elements reminding the world that Morris Lapidus favored them as neckwear.

Not everyone was enthralled with Lapidus’s work at the Fountainbleau. The editor of a leading architectural publication of the time, Douglas Haskell, according to historian Karal Ann Marling, called the architect and said:

Morris, what the hell were you thinking of? What were you doing? . . . And the interiors! My God! We walked in there and said ‘this is terrible!

The Fountainbleau has undergone many changes since its heyday. I prefer to stay focused on Lapidus and the first few decades of the hotel. Despite the intense architectural criticism leveled, the property was meant to be the ultimate “fun-in-the-sun” destination resort, mid-century American style. The guests arrived by automobile, in the brilliant Florida sunshine, and strolled into the theatrical lobby expecting a respite from gray and cold. Morris Lapidus delivered.

The Eden Roc Hotel, Miami Beach

The Eden Roc opened in 1955, the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc on the French Riviera having inspired the name. Morris Lapidus designed this property in a slightly more “sedate” fashion than the Fountainbleau next door, foregoing the curvilinear shape of the previous structure in favor of a more traditional rectilinear form. The critics were no more kind than usual and Lapidus stuck to his own ideas of what a Miami Beach resort hotel should look like. Even more importantly, the paying guests were the only critics of any real importance.

In my opinion, the Fontainebleau was not French and the Eden Roc was not Baroque. It was just my style. A style that is simply an expression of my own ideas, not an expression of a particular school of architecture. I developed a style that nobody can name, but which architects around the world are today attempting to copy.

Before the literal resurrection of south beach and The art Deco district. Morris Lapidus represented south Florida Architectural style. When you visited South Florida, his hotels played their roles perfectly. Thanks for reading.