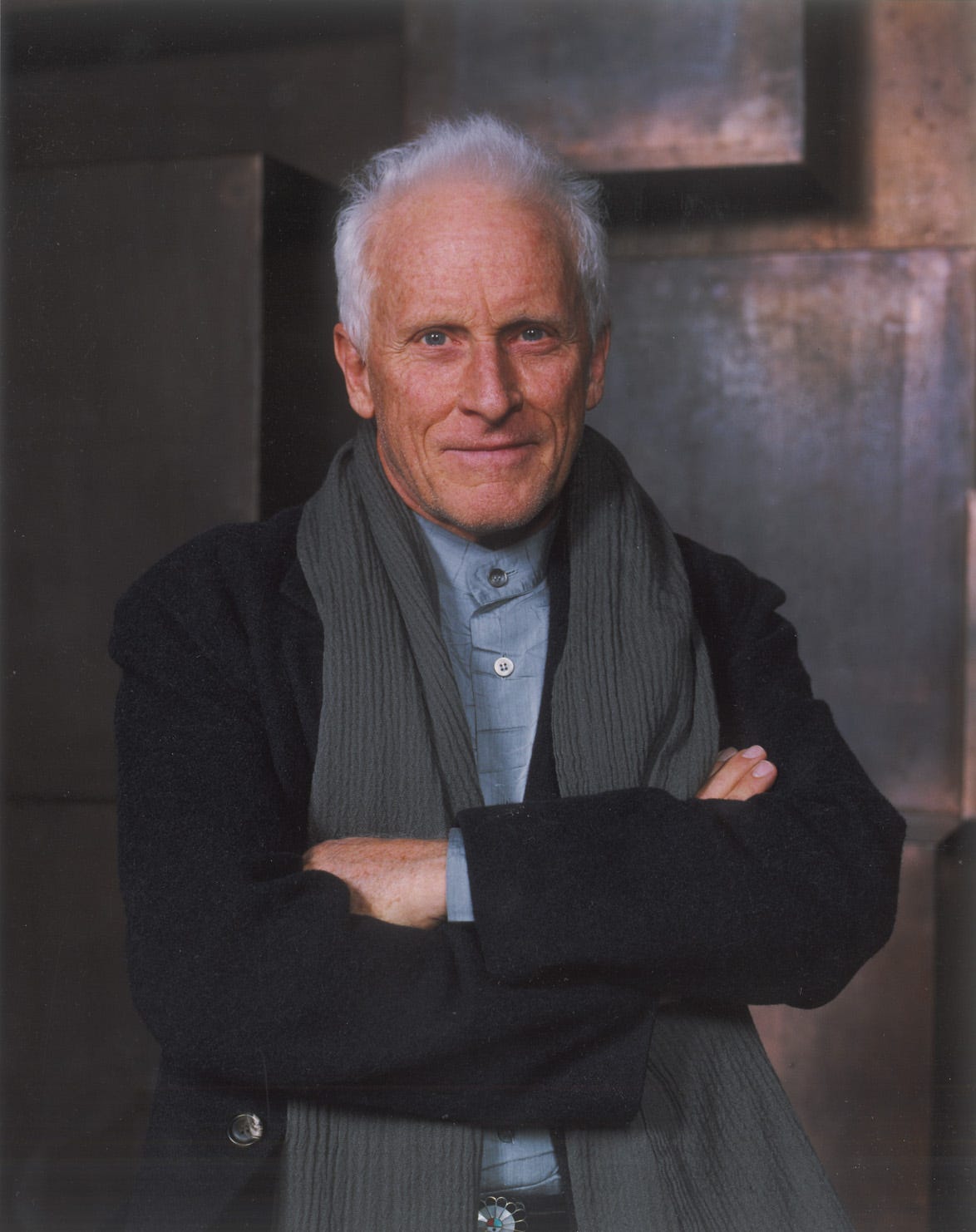

Although Antoine Predock was born in Missouri in 1936, he considered himself a native of Albuquerque, where he moved to attend college. His work has come to symbolize the built environment functioning within the natural environment of the American Southwest. I recall my first trip to Albuquerque vividly. First, the elevation of slightly over 5000 feet makes it the highest American capital city. Second, there was a very distinctive architectural style. At the time of my first visit, Mr. Predock had already stamped his style on the entire region, as I would soon learn. After all, he had set up his first office in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1967. Mr. Predock passed away last year. Let’s take a look at a few of his works.

George Pearl Hall

Named in honor of local architect and benefactor George Pearl, George Pearl Hall on the University of New Mexico campus was designed to celebrate both legacy architecture and a spirit of modernity. Christopher C. Mead Wrote that:

George Pearl Hall avoids the pre-packaged imagery of the Spanish-Pueblo Style, even as it negotiates the complex histories of architecture in New Mexico.

Austin City Hall

Austin City Hall opened in fall 2004. It’s covered in copper, glass, and Texas limestone and connects the lively downtown scene with Lady Bird Lake's natural setting.

Canadian Museum for Human Rights, Winnipeg

Writing for Architect Magazine, Thomas de Monchaux:

The Museum of Human Rights appears to have been designed from the inside-out—driven less by photogenic form than by a cinematically and psychologically immersive experience over time

Antoine Predock himself added:

It isn’t a museum of objects, it’s a museum about ideas. It’s a process building. It’s a procession building.

There is a “theory of the case” that Winnipeg wanted to take a page out of the Bilbao book and ask an architect to design a museum for them that would become an international destination. I am not sure what went on behind closed doors, but Winnipeg might not have gotten a building with the international buzz that the Frank Gehry Guggenheim created for Bilbao. But it appears to be a fine effort worth our applause, as a classic example of earth meets sky architecture.

American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming

Architect and editor John Hill had this to say about the project:

Started in 1986 and completed in 1993, the building makes a strong formal statement through the new cone-shaped “mountain” that is set on “a man-made mesa, a surrogate landform” with archival and curatorial spaces for the two programmatic entities housed in the building.

Nelson Fine Arts Center, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona

The Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University in Tempe began construction in 1985 and opened in 1989. The design won the 1989 American Institute of Architects Honor Award. The previously quoted John Hill described this project:

A complex program of museum, theater, and facilities for the departments of theater arts and dance led to a complex formal solution: steps and terraces, plazas and courtyards, concrete walls with stucco

I was lucky enough to see this work the year it opened; the building looked perfectly compatible with the Tempe, AZ environment, which was in keeping with Predock's philosophy.

Writing in the New York Times, Fred A. Bernstein said this about Mr. Predock:

His later buildings, some far from Albuquerque, used materials and finishes appropriate to their locations. But they maintained the geological, almost primordial look that characterized Mr. Predock’s best work.

It is relatively well known that Antoine Predock was an avid motorcycle rider. So much so that it became a significant part of his “brand.” He also believed that people should experience architecture as a “ride,” which strikes me as an incredibly accurate expression of how great architecture is best experienced. Fred A. Bernstein, again writing in the New York Times, said that Mr. Predock

Became known for buildings that resonated with the landscape of the American Southwest..……. his early buildings were extensions of the desert.

Quoting John Hill from World Architects Magazine again:

Predock's buildings, which can appear chaotic and complex in photographs at times, are understandable and exceptional when experienced.

The Antoine Prodock works that I have experienced seem to have sprung up from the landscape. Below is a keynote presentation Mr. Predock delivered at a design summit in 2018:

In conclusion, let’s rely on some advice on creativity that Mr. Predock gave to students:

Keep your flame alive. There’s all kinds of ways to do that. You may be paying your dues with an internship at a corporate firm. You’re wondering what you’re doing and where you’re going. You can keep your flame alive in other ways. You draw maybe or write poetry. Don’t ever just give that part up.

Antoine Predock’s March 5, 2024 obituary in the NY Times began with:

Antoine Predock, an Albuquerque-based architect who became known for buildings that resonated with the landscape of the American Southwest, earning him international acclaim and prestigious commissions as far away as Canada, Costa Rica and Qatar, died on Saturday at his home in Albuquerque. He was 87.

Perhaps the best review I have read of Mr. Presock overall work came again from Paul Goldberg in the New York Times when he said:

Mr. Predock’s “Southwestern buildings are not cute little adobe structures, cloying stage sets of a tourist’s Santa Fe; they are tough, hard-edged and self-assured.

I think we can leave it right here!

Architecture for the Soul is a reader-supported publication. Please consider supporting our efforts as a paid subscriber

There’s a strong sense that his buildings grow out of the ground, especially in projects like George Pearl Hall or the Nelson Fine Arts Center. Even with their heavy, weight-driven compositions, there’s always a feeling of movement.Predock doesn’t seem to be designing static spaces. It feels more like he’s organizing a structural experience meant to be moved through by the body and stirred by the wind